Ultra High Apogee Transfer Orbits

Launch loops are not limited by the Tsiolkovskii exponential; while high loop velocities require large radius ambit magnets and vertical deflection magnets, the main difference between an 8 km/s launch and an 11 km/s launch is doubled energy cost (electrical power, not cryofuel), but not an exponentially larger loop.

Hence, Earth orbits with very high apogees are slow, but not expensive to get to. Small velocity changes at high apogee are large velocity changes at lower perigees. If you can tolerate the delivery delay, payload transfer via a high apogee orbit can save propellant, while ejecting that propellant far from Earth orbit.

In 2018, we presume an infinite supply of propellant, and an Earth orbit environment with an infinite capacity for exhaust. However, a less wasteful approach conserves resources and preserves the space environment into the distant future.

From 100 km altitude (6478 km radius, ignoring residual atmospheric drag and J₂ oblateness), the launch and insertion velocities are:

|

km |

m/s |

|

|

|

apogee |

launch |

insert |

|

400 km LEO |

6778 |

7460 |

87 |

|

server sky |

12789 |

8566 |

1005 |

|

GEO |

42164 |

9856 |

1488 |

|

Moon |

384400 |

10529 |

833 |

|

Earth-Sun Lagrange 1 |

1500000 |

10597 |

251 |

|

|

||||

transfer to GEO via L1 apogee parking orbit |

||||

L1/10,000 km parking |

1500000 |

10597 |

28 |

|

L1 apogee to circular |

42164 |

46 |

-1214 |

|

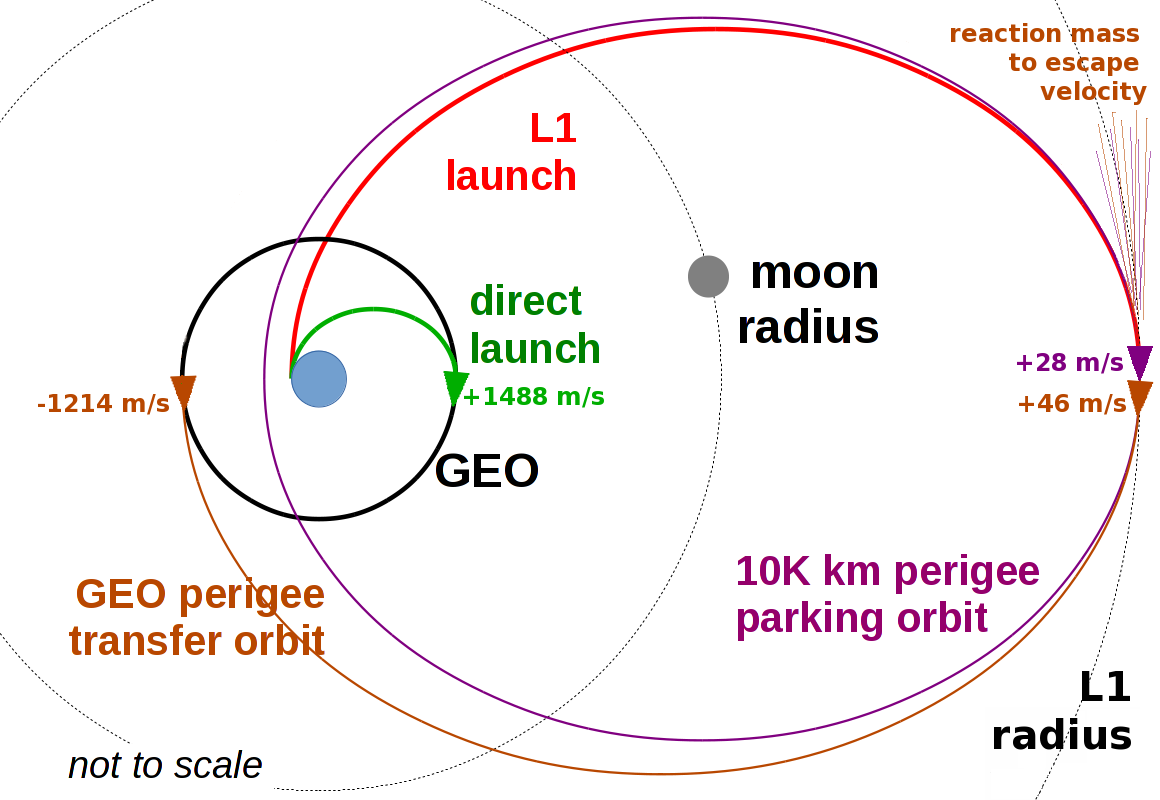

The last line differs from the others; that is a mission that involves a loop launch to L1 radius apogee, then a 28 m/s of delta V to raise perigee from loop radius to a 10,000 km perigee parking orbit. Later, after many orbits and synchronization (matching arrival time AKA true anomaly) with the GEO destination, add another 46 m/s thrust to raise perigee to GEO radius. Adding this angular momentum and velocity is cheap at high apogee radius. Indeed, the velocity change may be achieved naturally, without reaction mass thrust, from clever use of the 4-body problem (vehicle to Earth, Sun, and Moon).

After these manuevers, the vehicle GEO/perigee velocity is 4288 m/s; it must shed angular momentum and velocity to enter circular GEO orbit (V circular = 3075 m/s), unlike a vehicle arriving in an elliptical orbit from the loop at Earth, which has an apogee velocity at GEO of 1587 m/s and must gain angular momentum and 1488 m/s of velocity to enter circular GEO orbit.

Confusing openoffice spreadsheet here.

What if we could transfer angular momentum from L1 vehicle traffic to direct-from-launch vehicle traffic?

Imagine a rotating tapered tether at GEO, which can capture vehicles launched directly from Earth (adding delta V and angular momentum to the arriving vehicle) or from an L1/GEO transfer orbit (subtracting delta V and angular momentum from an arriving vehicle). If the ratio of the mass streams is 1214 to 1488 (23% more vehicle mass arriving via an L1 apogee), then no makeup momentum or thrust needs to be added at GEO. This assumes elliptical equatorial-plane orbits that "kiss" GEO; with additional radial velocity, we may be able to balance rotating tether angular momentum at GEO as well (this needs further study).

So, no additional delta V added for direct upward vehicles. about 74 m/s delta V added at L1 apogee for indirect-via-L1 vehicles.

L1 "orbit" is about 300 m/s sidereal relative to the Earth, faster than an isolated orbit without the Sun's gravitational influence. Vehicles in Earth orbit with perigees at that radius will return to Earth, though solar and lunar gravitational perturbations will be significant. The actual orbit and delta V must be computed and adjusted for every individual mission. On the other hand, we can probably manage the object cloud to minimize collisions and maximize launch rates throughout the day, month, and year. Some of the vehicles will make many orbits before arriving at GEO; these will be unmanned cheap cargo orbits. Given that payloads today sometimes wait years for orbital slots, launching them into orbit cheaply for eventual delivery (perhaps months later) may be a cost-effective tradeoff - better late than never!

Note that rocket exhaust emitted at L1 will leave the Earth-Moon system at much higher than escape velocity, and end up in solar orbit with a perihelion at Earth's solar radius and an aphelion a few million kilometers further out. After a few hundred years, it might pass through the Earth/Moon system system again; chances are, it will be perturbed by Jupiter and scattered far too thinly to ever detect again. I dislike wasting mass (probably argon from a VASIMR engine) that way, but there won't be much of it.

For extra bonus points, presume a high exhaust velocity and a huge shipping rate, calculate the argon loss rate, and compare that to the production rate of atmospheric argon via natural potassium 40 radioactive decay. Is this "billion year sustainable"? ![]()

Lunar "slingshot" boost ?

A seeming alternative (that doesn't actually work very well) is a slingshot orbit past the Moon, speeding up the vehicle at the expense of some lunar momentum. However, the Moon is in an orbit with inclination varying from 18.3 to 28.6 degrees; it crosses the equatorial plane only twice a month, and the launch loop must be at a precise Earth-rotational angle to take advantage of that. A popular idea, but not very practical