|

Size: 7735

Comment:

|

Size: 15616

Comment:

|

| Deletions are marked like this. | Additions are marked like this. |

| Line 6: | Line 6: |

| Launch loops can scale up to enormous size (and cost), but don't scale much smaller than 5 tonne vehicles at 3 gees, a consequence of the scale of the atmosphere they rise through. | Launch loops can scale up to enormous size (and cost), but don't scale much smaller than 5 tonne vehicles at 3 gees, a consequence of winds in the atmosphere they rise through. |

| Line 12: | Line 12: |

| || || seconds ||<)> km ||<)> km ||<)> km/s ||<)> km/s || inclination || <)> km/s || | || || seconds ||<)> km ||<)> km ||<)> km/s ||<)> km/s || inclination ||<)> km/s || |

| Line 29: | Line 29: |

| The earth rotates once per stellar day (relative to the fixed stars) every [[ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Earth%27s_rotation#Stellar_and_sidereal_day | 86164.0989 seconds ]]. The launch loop rotates under the perigee of an orbit at exactly this rate. In order to add another component to an orbiting assembly, it should be launched as the assembly is near perigee, overhead, timed within milliseconds. This can only happen if perigee is synchronized with the Earth's stellar day rotation, with corrections for tidal effects and the equatorial bulge.' | The earth rotates once per stellar day (relative to the fixed stars) every [[ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Earth%27s_rotation#Stellar_and_sidereal_day | 86164.0989 seconds ]]. The launch loop rotates under the perigee of an orbit at exactly this rate. In order to add another component to an orbiting assembly, it should be launched as the assembly is near perigee, overhead, timed within milliseconds. This can only happen if perigee is synchronized with the Earth's stellar day rotation, with corrections for Lunar tidal effects and the equatorial bulge. |

| Line 31: | Line 31: |

| The minimum launch loop is designed for 5 tonne vehicles at a 45 second cadence. We will presume one vehicle per 1 stellar day cycle. | An additional complication is apsidal precession. As a highly elliptical orbit passes near the oblate earth, the orbit will turn a little more than the classic case; as a consequence, the apogee and the next perigee will be a few seconds eastward. This will lengthen the orbit somewhat. |

| Line 33: | Line 33: |

| ''' Note:''' While it may be possible to launch groups of vehicles more closely timed than 45 seconds, each vehicle adds tension and deflection to the track/ The tension is maximum at low speed near west station. Tight grouping will increase stress over the entire track, and reduce total throughput. In 45 seconds, the earth turns 0.19 degrees, and apogee "turns" 780 kilometers. Since higher orbits are slower orbits, it may be possible to send a string of vehicles to a series of cascaded higher orbits that intersect the construction orbit at somewhat higher velocities, and maneuver them towards rendezvous a few orbits later, permitting higher total throughput during a multi-month construction program. I'll leave such complexities to future mission designers. | A fully-powered minimum launch loop can launch a 5 tonne vehicle every 45 seconds; that is 1920 vehicles per solar day, 5 less than that per stellar day. That can feed thousands of construction orbits and thousands of projects. |

| Line 35: | Line 35: |

| A fully-powered launch loop can launch a 5 tonne vehicle every 45 seconds; that is 1920 vehicles per solar day, 5 less than that per stellar day. That can feed thousands of construction orbits and thousands of projects. | While it may be possible to launch groups of vehicles more closely timed than 45 seconds, each vehicle adds tension and deflection to the track. The tension is maximum at low speed near west station. Tight grouping will increase stress over the entire track, and reduce total throughput. In 45 seconds, the earth turns 0.19 degrees, and apogee "turns" 780 kilometers. Since higher orbits are slower orbits, it is possible to send a string of vehicles to a series of cascaded higher orbits that intersect the construction orbit at somewhat higher velocities, and use somewhat more apogee delta V to inject them into the same construction orbit, permitting higher total throughput during a multi-month construction program. |

| Line 37: | Line 37: |

| There should be at least three launch loops, providing redundancy in case of failure. If two operate on the same latitude and different longitudes, that can double the vehicle delivery rate per construction orbit. | I will presume we can launch 20 vehicles spaced over a 15 minute range ( +/- 7.5 minutes ) per launch loop, 20 per stellar day. There should be at least three launch loops, providing redundancy in case of failure. If two operate on the same latitude and different longitudes, that can double the vehicle delivery rate per construction orbit. So, with enough power supply, two loops can deliver 200 tonnes per day to each of 96 construction orbits, about 10 million tonnes per year if all three loops operate at continual maximum power. More loops can be added, and they can be scaled MUCH larger if they are reliable and well defended. |

| Line 46: | Line 47: |

| Leaving the loop, vehicles will climb out through the upper atmosphere and encounter significant drag; they will need a sharp hypersonic nose cone with a heat resistant ablative spherical cap. However, the dynamic pressure and gee forces will be small, permitting the use of low-cost materials. An amusing possibility is "nanowood", ordinary wood from trees that has been treated to remove most of the "live" material and leave only strong structural cellulose. As strong as ordinary wood, less dense and more insulating than styrofoam. | Leaving the loop, vehicles will climb out through the upper atmosphere and encounter significant drag; they will need a sharp hypersonic nose cone with a heat resistant ablative spherical nose cap. However, the dynamic pressure and gee forces will be small, permitting the use of low-cost materials. An amusing possibility is "nanowood" [[ https://phys.org/news/2018-03-nanowood-humanity-carbon-footprint.htm | 1]],[[http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aar3724 |2]] wood from trees that has been treated to remove most of the "live" material and leave only strong structural cellulose. As strong as ordinary wood, less dense and more insulating than styrofoam. |

| Line 48: | Line 49: |

| Should the apogee insertion rocket fail, vheicles will re-enter somewhere to the west of the loop, probably exploding in the lower atmosphere. Passenger vehicles must be capable of safely re-entering, of course, making them vastly more expensive than cargo vehicles. Vehicles will also briefly pass through the center of the van Allen radiation belts, | Should the apogee insertion rocket fail, cargo vehicles will re-enter somewhere to the west of the loop, probably disintegrating in the lower atmosphere if they are not equipped with heat shields and parachutes. Of course, passenger vehicles must be capable of safely re-entering, making them much more expensive than cargo vehicles. Vehicles will also briefly pass through the center of the van Allen radiation belts, but if they are launched into a high orbit at high speed, they will pass through the belts relatively rapidly. |

| Line 50: | Line 51: |

| MoreLater | Passengers will get a one-time radiation dose exceeding that of the Apollo astronauts, because launch towards a 6458x75950 km construction orbit from 8 degrees south passes them briefly through the equatorial plane at 24150 km altitude, about 3.5 Earth radii, the center of the van Allen belt. Apollo astronauts passed through this altitude well below the equatorial plane. Hopefully, astronauts aimed for construction orbits will only pass through twice per extended mission; in construction orbit they will have much more shielding. If the two-time dose is too much, they will need heavy, hydrogen-rich shielding; this extra mass (which could be fuel or plastic cargo) will reduce the number of astronauts that can be launched per vehicle. |

| Line 55: | Line 56: |

| All components will need some initial thrust to raise perigee above LEO. At the first apogee, the initial perigee radius of 6378+80 = 6458 km is raised to 8378 km with a relatively small and inexpensive thrust package, producing 114 m/s of delta V. It is more important that this initial thrust device is inexpensive, high thrust, reliable and accurate, rather than high I,,ISP,,. Vehicles should arrive ready for collection. | All components will need some initial thrust to raise perigee well above LEO, away from satellites crowded into high inclination orbits near the Earth. At the first apogee, the initial perigee radius of 6378+80 = 6458 km will be raised to 8378 km with a relatively small and inexpensive thrust package, about 114 m/s of ΔV. It is more important that this initial thrust device is inexpensive, high thrust, reliable and accurate, rather than high I,,ISP,,. |

| Line 57: | Line 58: |

| The first component launched will be a thrust "tractor", with enough precision ΔV capability to rendezvous with subsequent vehicles. Tanks of fuel will be delivered next; these will double as radiation shielding for construction workers and radiation sensitive components. | The construction orbit will have a 86164.0989 second period, one stellar day, with perigee at 8 degrees south latitude. The launch loop (also at 8 degrees south latitude) will rotate underneath perigee once per day, to add another string of 5 tonne components to the assembly. |

| Line 59: | Line 60: |

| The construction orbit will have a 86164.0989 second period, one stellar day, with perigee at 8 degrees south latitude. The launch loop (also at 8 degrees south latitude) will rotate underneath perigee once per day, to add another 5 tonne component to the assembly. | The first component launched will be a thrust "tractor", with enough precision ΔV capability to rendezvous with subsequent vehicles and rendezvous with the accumulating construction station. Subsequent vehicles should arrive ready for collection by orbital tugs stationed beforehand in construction orbit, which will perform the low ΔV capture, maneuvering and final rendezvous with the construction station. |

| Line 61: | Line 62: |

| Tanks of fuel will be delivered next; these will double as radiation shielding for construction workers and radiation sensitive components as the construction orbit passes through the radiation belts, once per day. | |

| Line 62: | Line 64: |

| The high eccentricity construction orbit moves at high velocity near the earth, low velocity far from it, less than 6 hours per day below geostationary altitude. While the total radiation dose will be higher than an alternative circular construction orbit at GEO altitude, the dose for 18 hours a day will be much lower. Astronauts aboard the construction station will sleep in tubes between the fuel and water tanks for the 6 hours of high radiation dose, and will receive much less total radiation dose than they would in the circular orbit. | |

| Line 63: | Line 66: |

| MoreLater | Although I have not done the calculation, if there are hundreds of thousands of tonnes of low-Z atoms orbiting daily through the center of the radiation belts, that will absorb or scatter most of the low and medium energy protons. This could rapidly attenuate the total trapped ion population in the radiation belts. In time, this could make space travel much safer. Eliminating most of the belt also greatly reduces the equatorial ring current, which is the mechanism that couples coronal mass ejections from the Sun to "Carrington Event" magnetic field changes on the Earth. If this works as expected, this will protect the terrestrial power grid from the large ground loop voltages that can damage it during solar storms. Construction orbits will be used to assemble high altitude mega-structures, such as space solar power satellites and space colonies. They will also be the source and the return destination for reusable interplanetary vehicles, such as [[https://buzzaldrin.com/space-vision/rocket_science/aldrin-mars-cycler/ | Aldrin Mars Cyclers ]]. What does a construction orbit look like? '''Here is a plot of the (stellar) daily position of construction stations as viewed from the fixed stars:''' [[attachment:oneday05f.png || {{ attachment:oneday05f.png | | width=800 }}]] . Click for larger view, or download. The grid is in "Earth equatorial radii", 6378 kilometers per grid cell. 96 dots per 86184 stellar day period, a bit less than 15 clock minutes between dots, with every 4th dot accented to represent a "stellar hour". A comsat in geostationary orbit is shown; comsats will be needed to relay communications to Earth stations below during part of the orbit. Note that a construction station spends less than 6 hours below GEO. Construction workers will sleep in shielded areas during this portion of the orbit. '''Here is a plot of the same orbit viewed relative to the rotating Earth:''' [[attachment:oneday05e.png || {{ attachment:oneday05e.png | | width=800 }}]] . Click for larger view, or download. The actual orbit is not kidney bean shaped, of course; this is merely how it appears from our rotating vantage point. The construction orbit perigee (and apogee 12 stellar hours later) are both at the same latitude as the launch loop, shown here at 120 degrees west longitude, due south of the west coast of the United States. However, the station is only visible for about 10 minutes before and after perigee, dropping below the horizon for 5 hours before and after. For about 12 hours of every orbit, communications to the launch loop area itself must be relayed through communication satellites in geosynchronous orbit, or via other stations in construction orbit. Note also that due to the inclination of the construction orbit, apogee will be 8 degrees north of the equator. This constellation of orbits (each of the points represents a large, permanent construction station) will be the hub of activity associated with a launch loop. Additional launch loops will be built to the east closer to the South American coast, and west towards French Polynesia; so there will be many non-intersecting constellations. Traffic management for these orbits will require global coordination, and will require continual tweaking to correct for tidal perturbations from the Moon, Sun, and Jupiter, but we will eventually orbit billions of tonnes of construction stations as waypoints to the rest of the solar system. Think '''BIG'''. Here is the [[ oneday05.c | C program ]] that computed the numbers, and the [[ oneday05.gp | gnuplot control file ]] that produced the pretty pictures. I would like to change how the van Allen belts are depicted, as a sheaf of thin gray lines representing the density of the belt, but I have more important tasks to complete first. But how do we get from an inclined construction orbit to a circular equatorial GEO orbit? One way is with another small ΔV thrust at apogee to raise perigee, then make a second larger ΔV thrust as this orbit crosses the equatorial plane at GEO radius to circularize the orbit. . '''My hunch is that we should leave the inclination, and some of the eccentricity,''' so that the target orbit follows a Lissajous pattern in the sky - for space solar power, the idea is to concentrate availability during the peak load period between 5 to 10 pm on the Earth below. If the SSPS appears at a higher latitude in the sky, this reduces interference with communication satellites to the south, and reduces the slant angle at which the beam arrives, reducing the size of both the power satellite transmitter and the rectenna farms below. Such complexities may bother those who like simple pictures, but they are how global economies comprising billions of contributors actually work. Oversimplification is for children and dictators, not profit-maximizing entrepreneurs and the clever engineers they hire. '' '''All that said,''' '' less clever engineers prefer circular equatorial orbits, so that's what the following maneuvers will deliber |

| Line 67: | Line 102: |

The orbits will look approximately like so, in relation to the fixed stars; inclination is not shown: [[attachment:Orbit12.png || {{ attachment:Orbit12.png | | width=800 }}]] . Click for larger view, or download. [[ Orbit12.odg | libreoffice drawing file ]] |

High Apogee Construction Orbit with a 5 Tonne Launch Loop

The goal for this example will be assembling large microwave-transmitting space solar power satellites (SSPS). The same process can be used to assemble smaller 183 GHz millimeter wave SSPS, lunar landers, deep space probes, or very large vehicles for interplanetary missions.

Launch loops can scale up to enormous size (and cost), but don't scale much smaller than 5 tonne vehicles at 3 gees, a consequence of winds in the atmosphere they rise through.

Mission summary, 1 stellar day construction orbit . . spreadsheet |

|||||||

Mission Segment |

duration |

perigee |

apogee |

vp |

va |

perigee |

entry Δv |

|

seconds |

km |

km |

km/s |

km/s |

inclination |

km/s |

340 |

6428 |

6458 |

0.471 |

10.667 |

8° S |

10.196 |

|

41657 |

6458 |

75950 |

10.667 |

0.906 |

8° S |

0.000 |

|

86164*N |

8378 |

75950 |

9.258 |

1.021 |

8° S |

0.114 |

|

69057 |

39500 |

75950 |

3.644 |

1.894 |

8° S |

0.873 |

|

21610 |

39500 |

45008 |

3.279 |

2.877 |

8° S |

0.366 |

|

permanent |

42164 |

42164 |

3.075 |

3.075 |

0° |

0.906 |

|

The very low cost of loop launch into high apogee orbits enables the assembly of large spacecraft and structures from 5 tonne components. If the apogee is very high, then a small Δv at apogee can raise the perigee of the orbit well above relatively crowded LEO orbits. For this discussion, assume 2000 km perigee altitude is adequate, and a 1 stellar day delivery cycle, hence a 84328 km -(6378+2000 km) = 75950 km apogee.

Launch from the Loop

The launch loop will be located south of the equator for gentle and steady weather. 8 degrees south latitude, east of French Polynesia and west of South America may be the best region for launch loop deployments.

The earth rotates once per stellar day (relative to the fixed stars) every 86164.0989 seconds. The launch loop rotates under the perigee of an orbit at exactly this rate. In order to add another component to an orbiting assembly, it should be launched as the assembly is near perigee, overhead, timed within milliseconds. This can only happen if perigee is synchronized with the Earth's stellar day rotation, with corrections for Lunar tidal effects and the equatorial bulge.

An additional complication is apsidal precession. As a highly elliptical orbit passes near the oblate earth, the orbit will turn a little more than the classic case; as a consequence, the apogee and the next perigee will be a few seconds eastward. This will lengthen the orbit somewhat.

A fully-powered minimum launch loop can launch a 5 tonne vehicle every 45 seconds; that is 1920 vehicles per solar day, 5 less than that per stellar day. That can feed thousands of construction orbits and thousands of projects.

While it may be possible to launch groups of vehicles more closely timed than 45 seconds, each vehicle adds tension and deflection to the track. The tension is maximum at low speed near west station. Tight grouping will increase stress over the entire track, and reduce total throughput. In 45 seconds, the earth turns 0.19 degrees, and apogee "turns" 780 kilometers. Since higher orbits are slower orbits, it is possible to send a string of vehicles to a series of cascaded higher orbits that intersect the construction orbit at somewhat higher velocities, and use somewhat more apogee delta V to inject them into the same construction orbit, permitting higher total throughput during a multi-month construction program.

I will presume we can launch 20 vehicles spaced over a 15 minute range ( +/- 7.5 minutes ) per launch loop, 20 per stellar day. There should be at least three launch loops, providing redundancy in case of failure. If two operate on the same latitude and different longitudes, that can double the vehicle delivery rate per construction orbit. So, with enough power supply, two loops can deliver 200 tonnes per day to each of 96 construction orbits, about 10 million tonnes per year if all three loops operate at continual maximum power. More loops can be added, and they can be scaled MUCH larger if they are reliable and well defended.

Because of the equatorial bulge, perigee will precess westward by a few seconds per day, and the construction orbit and launch time should be lengthened to match; better orbit designers than I will compute the exact amount of precession and adjust the numbers presented here. The slightly shorter "days" used by launch and construction crews will be inconvenient in a 24.0 hour world. Multi-thousand tonne sub-structures may require more than year to assemble, and be passed between "red", "green", and "blue" teams on the ground. The substructures can be assembled into megatonne-scale structures in GEO, synchronized 24.0 hour ground team schedules and independent of launch loop scheduling.

An 80,000 tonne space solar power satellite might be assembled in GEO from 80 large subcomponents, 1000 tonnes each. Each subcomponent would be assembled from 250 five tonne loop launches (estimated four tonnes of payload and one tonne of propellant and thrust stage) from two loops over 4 months. Two loops at 75 percent capacity can launch 2000 of these 1000 tonne components per year.

Ballistic Trajectory from Loop Launch to 75950 km

Leaving the loop, vehicles will climb out through the upper atmosphere and encounter significant drag; they will need a sharp hypersonic nose cone with a heat resistant ablative spherical nose cap. However, the dynamic pressure and gee forces will be small, permitting the use of low-cost materials. An amusing possibility is "nanowood" 1,2 wood from trees that has been treated to remove most of the "live" material and leave only strong structural cellulose. As strong as ordinary wood, less dense and more insulating than styrofoam.

Should the apogee insertion rocket fail, cargo vehicles will re-enter somewhere to the west of the loop, probably disintegrating in the lower atmosphere if they are not equipped with heat shields and parachutes. Of course, passenger vehicles must be capable of safely re-entering, making them much more expensive than cargo vehicles. Vehicles will also briefly pass through the center of the van Allen radiation belts, but if they are launched into a high orbit at high speed, they will pass through the belts relatively rapidly.

Passengers will get a one-time radiation dose exceeding that of the Apollo astronauts, because launch towards a 6458x75950 km construction orbit from 8 degrees south passes them briefly through the equatorial plane at 24150 km altitude, about 3.5 Earth radii, the center of the van Allen belt. Apollo astronauts passed through this altitude well below the equatorial plane. Hopefully, astronauts aimed for construction orbits will only pass through twice per extended mission; in construction orbit they will have much more shielding. If the two-time dose is too much, they will need heavy, hydrogen-rich shielding; this extra mass (which could be fuel or plastic cargo) will reduce the number of astronauts that can be launched per vehicle.

Construction orbit

All components will need some initial thrust to raise perigee well above LEO, away from satellites crowded into high inclination orbits near the Earth. At the first apogee, the initial perigee radius of 6378+80 = 6458 km will be raised to 8378 km with a relatively small and inexpensive thrust package, about 114 m/s of ΔV. It is more important that this initial thrust device is inexpensive, high thrust, reliable and accurate, rather than high IISP.

The construction orbit will have a 86164.0989 second period, one stellar day, with perigee at 8 degrees south latitude. The launch loop (also at 8 degrees south latitude) will rotate underneath perigee once per day, to add another string of 5 tonne components to the assembly.

The first component launched will be a thrust "tractor", with enough precision ΔV capability to rendezvous with subsequent vehicles and rendezvous with the accumulating construction station. Subsequent vehicles should arrive ready for collection by orbital tugs stationed beforehand in construction orbit, which will perform the low ΔV capture, maneuvering and final rendezvous with the construction station.

Tanks of fuel will be delivered next; these will double as radiation shielding for construction workers and radiation sensitive components as the construction orbit passes through the radiation belts, once per day.

The high eccentricity construction orbit moves at high velocity near the earth, low velocity far from it, less than 6 hours per day below geostationary altitude. While the total radiation dose will be higher than an alternative circular construction orbit at GEO altitude, the dose for 18 hours a day will be much lower. Astronauts aboard the construction station will sleep in tubes between the fuel and water tanks for the 6 hours of high radiation dose, and will receive much less total radiation dose than they would in the circular orbit.

Although I have not done the calculation, if there are hundreds of thousands of tonnes of low-Z atoms orbiting daily through the center of the radiation belts, that will absorb or scatter most of the low and medium energy protons. This could rapidly attenuate the total trapped ion population in the radiation belts. In time, this could make space travel much safer.

Eliminating most of the belt also greatly reduces the equatorial ring current, which is the mechanism that couples coronal mass ejections from the Sun to "Carrington Event" magnetic field changes on the Earth. If this works as expected, this will protect the terrestrial power grid from the large ground loop voltages that can damage it during solar storms.

Construction orbits will be used to assemble high altitude mega-structures, such as space solar power satellites and space colonies. They will also be the source and the return destination for reusable interplanetary vehicles, such as Aldrin Mars Cyclers.

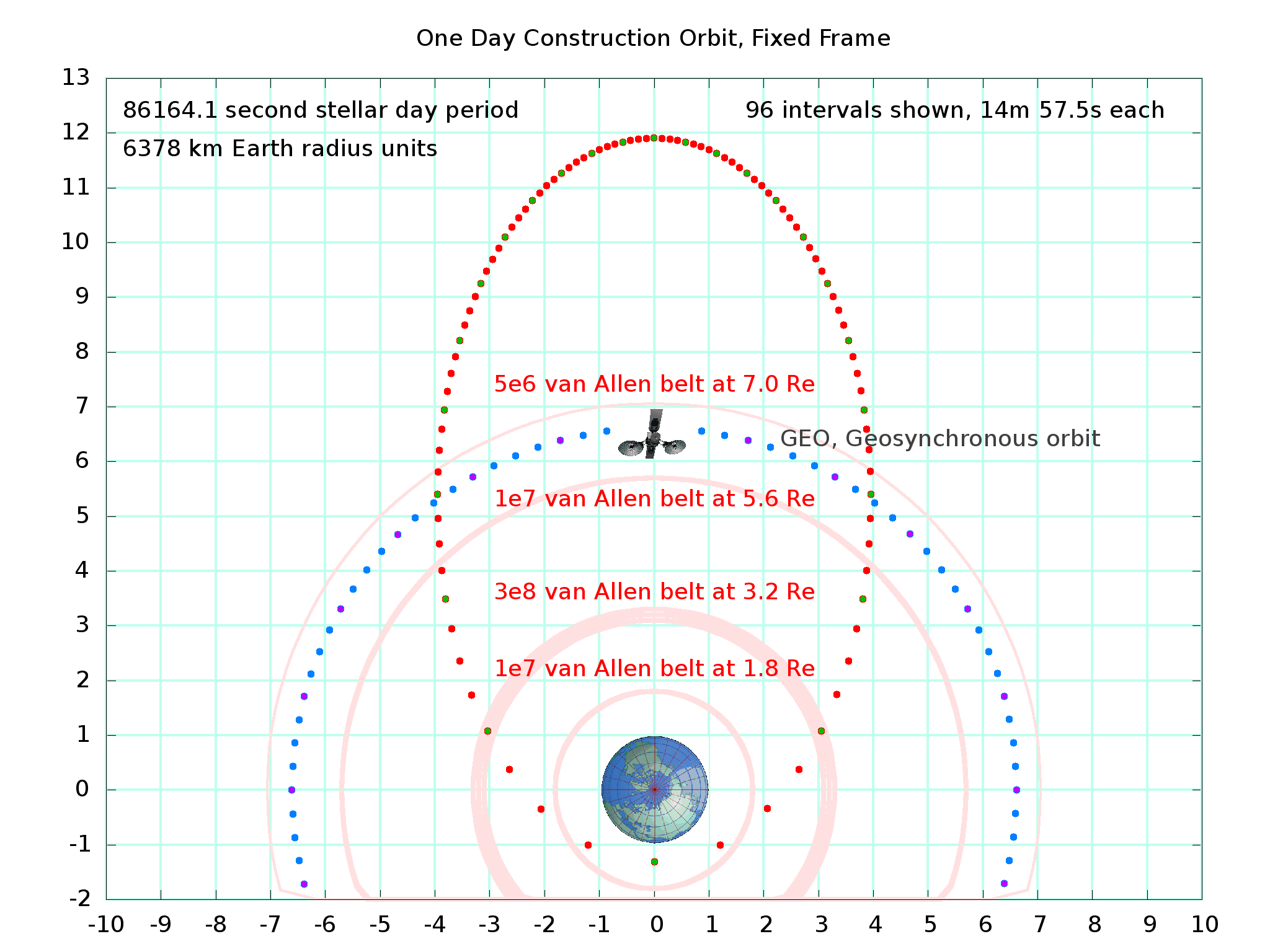

What does a construction orbit look like?

Here is a plot of the (stellar) daily position of construction stations as viewed from the fixed stars:

[[attachment:oneday05f.png ||  ]]

]]

- Click for larger view, or download.

The grid is in "Earth equatorial radii", 6378 kilometers per grid cell. 96 dots per 86184 stellar day period, a bit less than 15 clock minutes between dots, with every 4th dot accented to represent a "stellar hour". A comsat in geostationary orbit is shown; comsats will be needed to relay communications to Earth stations below during part of the orbit. Note that a construction station spends less than 6 hours below GEO. Construction workers will sleep in shielded areas during this portion of the orbit.

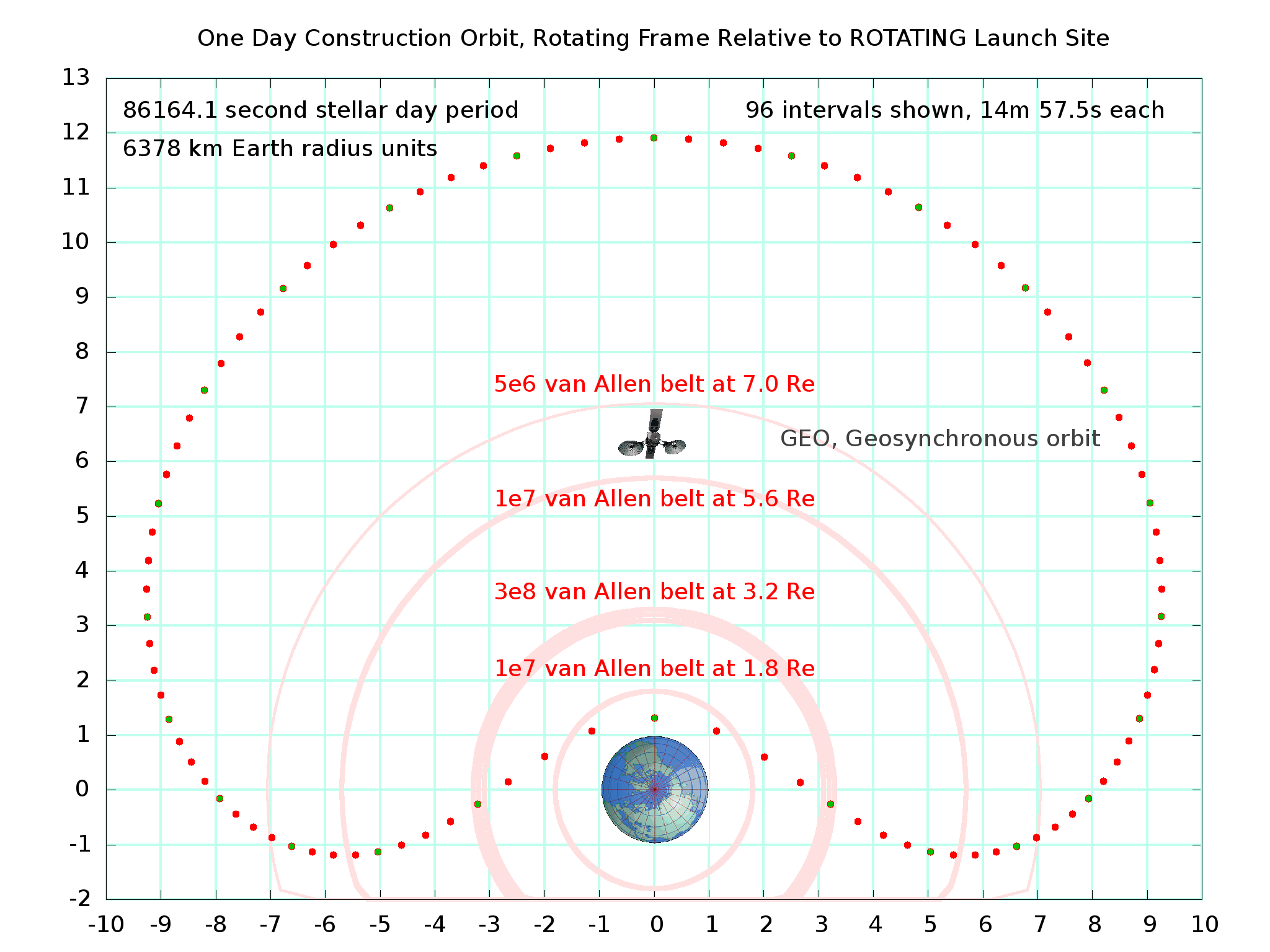

Here is a plot of the same orbit viewed relative to the rotating Earth:

[[attachment:oneday05e.png ||  ]]

]]

- Click for larger view, or download.

The actual orbit is not kidney bean shaped, of course; this is merely how it appears from our rotating vantage point. The construction orbit perigee (and apogee 12 stellar hours later) are both at the same latitude as the launch loop, shown here at 120 degrees west longitude, due south of the west coast of the United States. However, the station is only visible for about 10 minutes before and after perigee, dropping below the horizon for 5 hours before and after. For about 12 hours of every orbit, communications to the launch loop area itself must be relayed through communication satellites in geosynchronous orbit, or via other stations in construction orbit. Note also that due to the inclination of the construction orbit, apogee will be 8 degrees north of the equator.

This constellation of orbits (each of the points represents a large, permanent construction station) will be the hub of activity associated with a launch loop. Additional launch loops will be built to the east closer to the South American coast, and west towards French Polynesia; so there will be many non-intersecting constellations. Traffic management for these orbits will require global coordination, and will require continual tweaking to correct for tidal perturbations from the Moon, Sun, and Jupiter, but we will eventually orbit billions of tonnes of construction stations as waypoints to the rest of the solar system.

Think BIG.

Here is the C program that computed the numbers, and the gnuplot control file that produced the pretty pictures. I would like to change how the van Allen belts are depicted, as a sheaf of thin gray lines representing the density of the belt, but I have more important tasks to complete first.

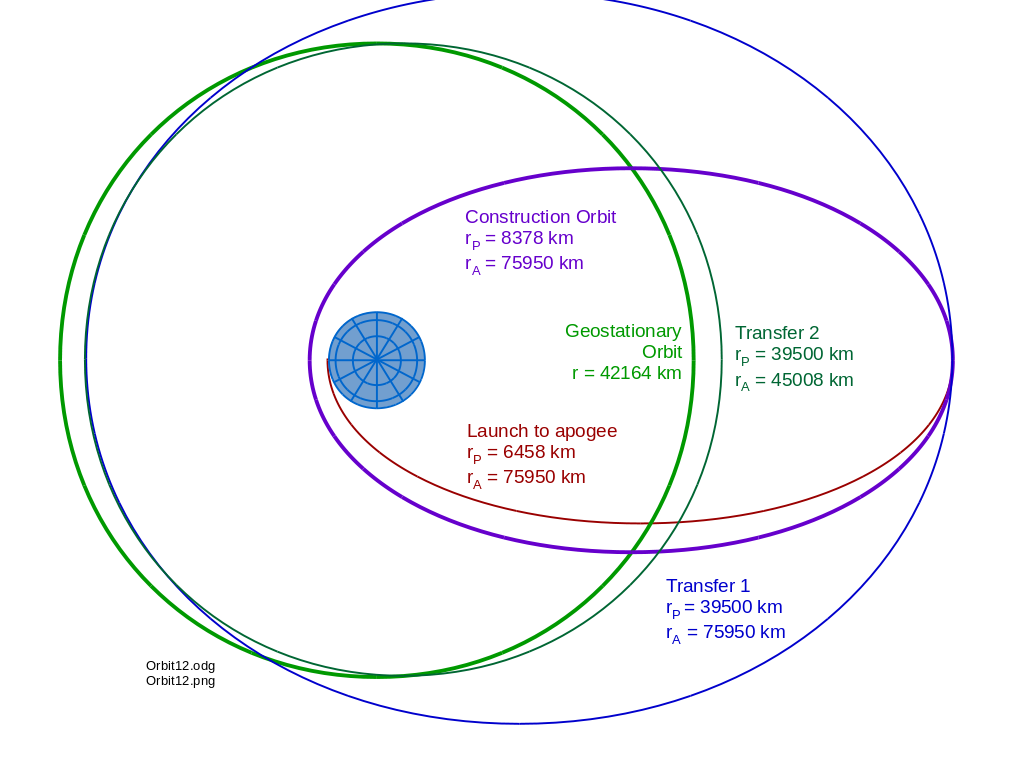

But how do we get from an inclined construction orbit to a circular equatorial GEO orbit? One way is with another small ΔV thrust at apogee to raise perigee, then make a second larger ΔV thrust as this orbit crosses the equatorial plane at GEO radius to circularize the orbit.

My hunch is that we should leave the inclination, and some of the eccentricity, so that the target orbit follows a Lissajous pattern in the sky - for space solar power, the idea is to concentrate availability during the peak load period between 5 to 10 pm on the Earth below. If the SSPS appears at a higher latitude in the sky, this reduces interference with communication satellites to the south, and reduces the slant angle at which the beam arrives, reducing the size of both the power satellite transmitter and the rectenna farms below. Such complexities may bother those who like simple pictures, but they are how global economies comprising billions of contributors actually work. Oversimplification is for children and dictators, not profit-maximizing entrepreneurs and the clever engineers they hire.

All that said, less clever engineers prefer circular equatorial orbits, so that's what the following maneuvers will deliber

Transfer orbit 1

The orbits will look approximately like so, in relation to the fixed stars; inclination is not shown:

[[attachment:Orbit12.png ||  ]]

]]

Click for larger view, or download. libreoffice drawing file

Transfer orbit 2